A lot of ink has been spilled on the economic and inflation outlook since President Trump shocked markets in April with a dramatic change in US trade policy. But while tariffs have increased and the outlook has become a guessing game, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy has been a rock of stability and remained frozen. That’s not necessarily a positive, but for the moment it’s one of the few things that’s been reliably boring on the macro landscape.

Fed funds futures continue to price in a high probability that the central bank will again leave its target unchanged at next week’s policy meeting. More of the same is expected for the July FOMC meeting. The crowd expects a cut in September, although three months out in the current climate might as well be three years and so caveat emptor is flashing brightly for that horizon.

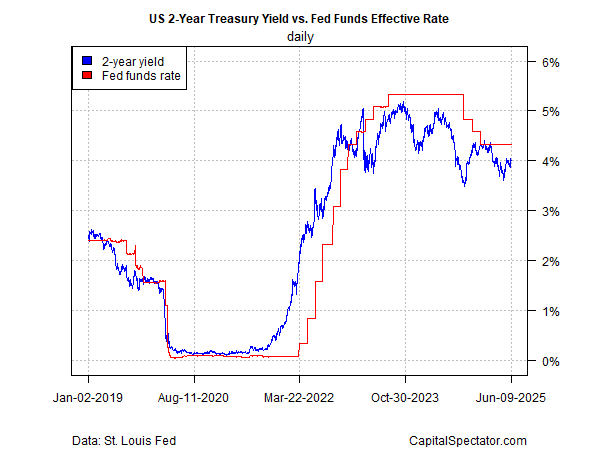

Meanwhile, the Treasury market’s policy-sensitive 2-year yield continues to price in rate cuts at some point for the near future.

The 2-year rate traded at 4.01% yesterday (June 9), close to the highest level since March, but still well below the median 4.33% effective Fed funds rate – a sign that the crowd anticipates a dovish shift in policy in the not-so-distant future.

Fed officials, however, continue to push back on the idea and say that they’re in no rush to change policy. For example, Raphael Bostic, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta last week wrote:

“There is a great deal of uncertainty out there, making it quite difficult to forecast the economy with confidence. Given that, I continue to believe the best approach for monetary policy is patience. As the economy remains broadly healthy, we have space to wait and see how the heightened uncertainty affects employment and prices.”

Other central bank officials have offered similar comments, but the Treasury market persists in pricing in cuts. Yet the conundrum that’s persuading the Fed to stand pat continues, namely: Will inflation accelerate due to tariffs? Or is the bigger risk that tariffs slow the economy?

The policy response to each of these outcomes are in conflict – rate hikes vs. rate cuts, respectively. A third possibility, which isn’t easily dismissed, is a degree of stagflation – softer growth and higher inflation. In that case, leaving policy unchanged could be the right prescription, and for the moment the Fed appears comfortable with that middle way.

Policy doves are quick to point out that inflation data continues to show minimal, if any, upside pressure from tariffs. Yesterday’s survey data for May via the New York Fed, for instance, highlights a sizable decline in year-ahead expectations for consumers. The glitch is that the slide to a 3.2% outlook remains well above the Fed’s 2% target.

Hard data for consumer inflation looks better, but core CPI — a widely follow measure for estimating the future trend — is still rising a 2.8% pace year-over-year. Until that moves closer to the Fed’s 2% target, central bankers will be in no rush to cut rates.

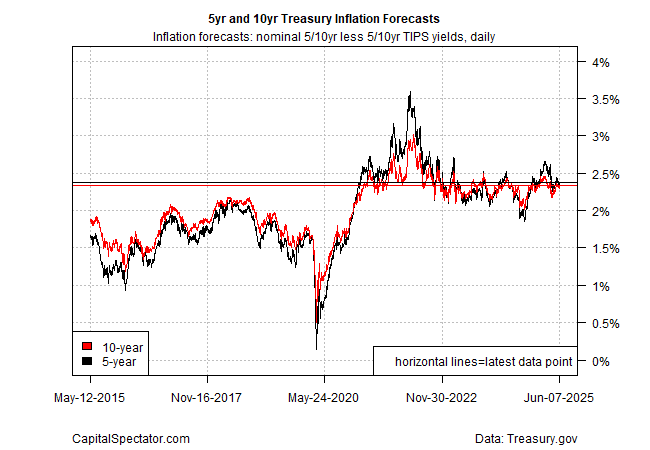

The Treasury market’s implied inflation forecast has been creeping higher lately, printing in the low 2% range, based on the spread for nominal less inflation-indexed yields. The 5-year maturities are currently projecting inflation at a 2.38% pace – a middling level relative to the past two months.

Watching and waiting may be frustrating for President Trump, who continues to call for rate cuts, but the Fed is arguably wise to wait for incoming data for more clarity. It’s almost certainly too early to make definitive decisions about the impact from tariffs for inflation and the economy, in no small part because tariff policy remains a fast-moving target. As we write, US-China trade talks are continuing in London, for instance.

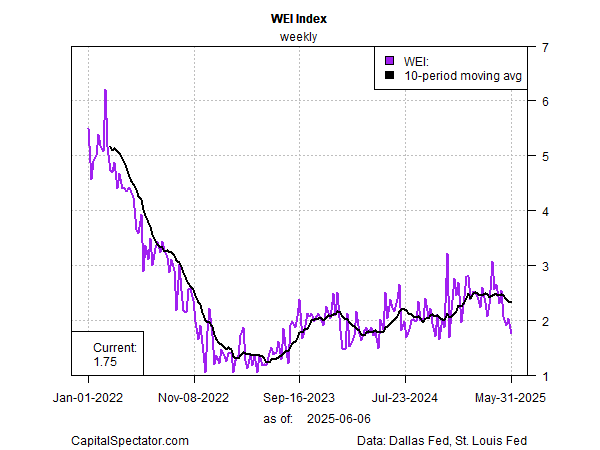

Meanwhile, there are signs that economic growth is downshifting. The Dallas Fed’s Weekly Economic Index fell again through May 31, suggesting that softer macro conditions are starting to resonate.

There’s also the mega-spending bill winding its way through the Senate. If enacted, some forecasters warn that it will stoke inflation expectations. Fiscal hawks are hoping to reduce the spending, but President Trump and his allies think it legislation is fine as written.

“I encouraged [Senators] to make as few modifications as possible, remembering that I have a very delicate balance on our very diverse Republican caucus over in the House,” said House Speaker Johnson in an interview on May 25.

“The best outcome for the bond market is they can’t agree,” said Brij Khurana, a fixed-income portfolio manager at Wellington Management. Gridlock between fiscal hawks and Senators willing to pass the bill might force negotiations to lower spending, which would likely be greeted positively by the bond market.

Watching and waiting, in other words, still looks like a reasonable if risky policy decision.