The Trump administration has been putting the privatization of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the headlines.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has said that he needs to make sure the transition won’t raise mortgage rates.

This is an example, imho, of overestimating the importance of interest rates and having policy discussions that have the pretense of being empirical when they aren’t.

Interest Rates

The benefit of Fannie and Freddie isn’t interest rates. Before 2008, Fannie and Freddie might have lowered the typical mortgage rate by 0.25%. Since 2008, federal regulators make sure private lenders don’t originate mortgages with much default risk. Fannie and Freddie don’t either.

But since they were exempted from some of the regulatory liabilities, lenders have been willing to originate mortgages for Fannie and Freddie that they wouldn’t keep on their own books. And Fannie and Freddie charge handsomely for it.

Relative to jumbo loan rates, on loans that are too large to sell into Fannie and Freddie securities, rates on conforming loans have sometimes been higher and sometimes been lower since 2008. And Fannie and Freddie have collected extra fees.

It’s possible they could be privatized without raising mortgage rates. The effect of federal efforts now is to raise mortgage spreads above the pre-2008 norms.

And the 30-year mortgage actually raises the typical mortgage rate and the typical monthly payment for home buyers relative to other options because it forces interest rate risk and prepayment risk onto lenders. It forces borrowers to pay for an inflation hedge position in order to fix their monthly payments over time.

It’s not a particularly well-optimized product, in my opinion, in terms of what new homebuyers value. (Over the past several decades, the 30-year mortgage rate has typically been nearly 2% higher than adjustable rates, just so borrowers can be promised a fixed payment for 3 years in a world where the price of everything else and their incomes go up routinely at varying rates.)

But none of that matters that much. A quarter point here or there isn’t going to make or break the American housing market. A quarter point isn’t what increased the homeownership rate from the low 40s after World War II to the mid-60s.

A standardized set of underwriting norms that banks could use to accept some default risk without creating an adverse selection problem did that.

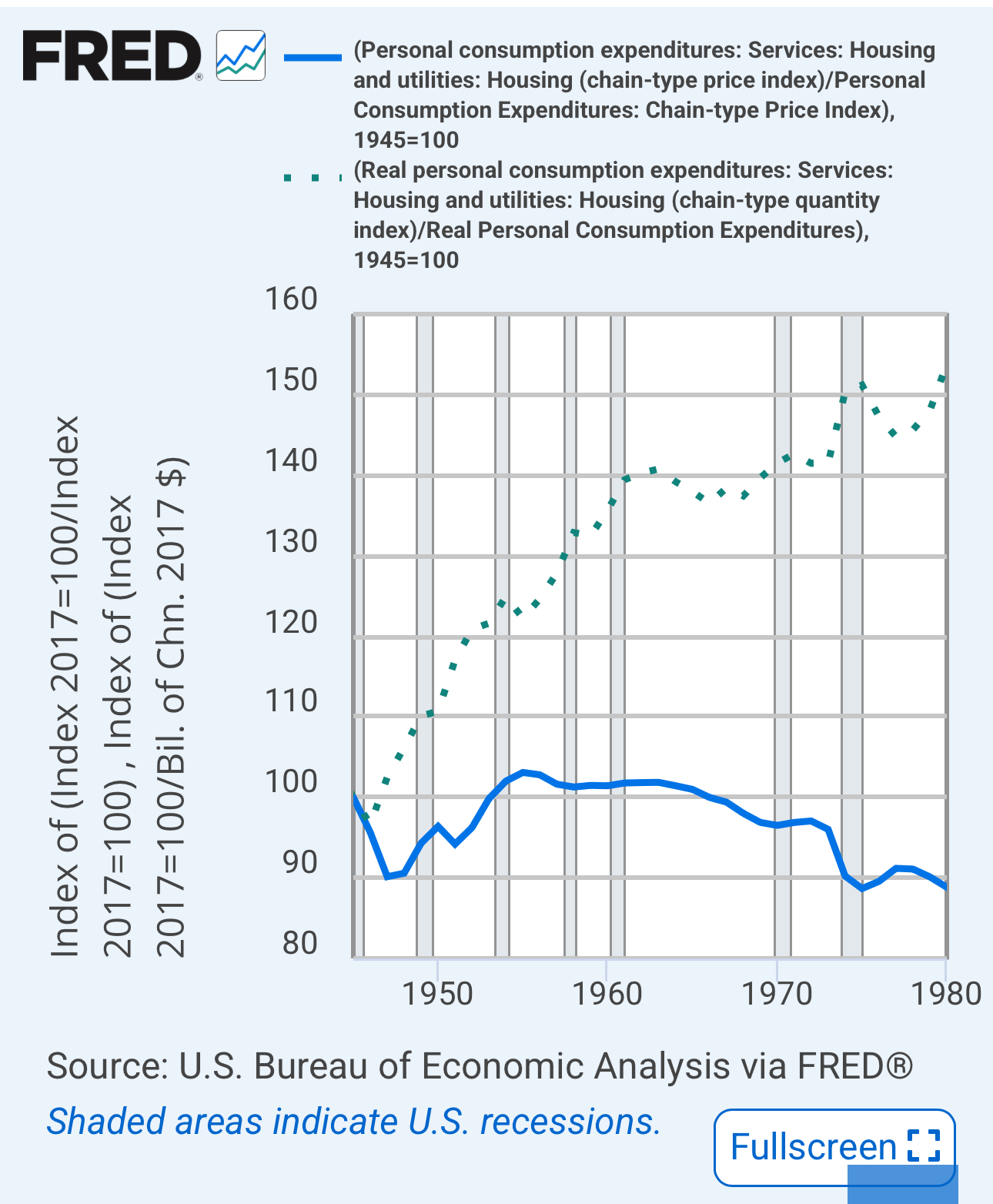

It worked pretty well for decades. Families got more house (dotted line) for lower rents (solid blue lines).

During that period when housing was booming and families were getting more and better homes, interest rates climbed sharply, but they reflected an inflation premium.

When new home constructions aren’t entirely obstructed, lower real interest rates lower rents. The price of homes is anchored to the price of lumber, labor, concrete, etc. So, a declining discount rate means the same house at the same price requires a lower rent yield.

A higher inflation premium might affect the ability of new buyers to make payments, and this seems to be the focus of a lot of analysis. I don’t see much evidence in historical trends that it matters much for the broader market.

Then there was a 40-year downtrend in mortgage rates. The first 20 years saw a decline in the inflation premium. The next 20 years saw a decline in real rates.

By the 2000s, there were places where low real rates could still lower rents, and a growing number of places where rents were rising because of blocked supply. Where supply was blocked, there was likely a bit of additional home price appreciation from the late 1990s to about 2002, when real interest rates took a step down. Generally, though, prices have been driven by rents that rise because of local supply constraints.

Mortgage Access

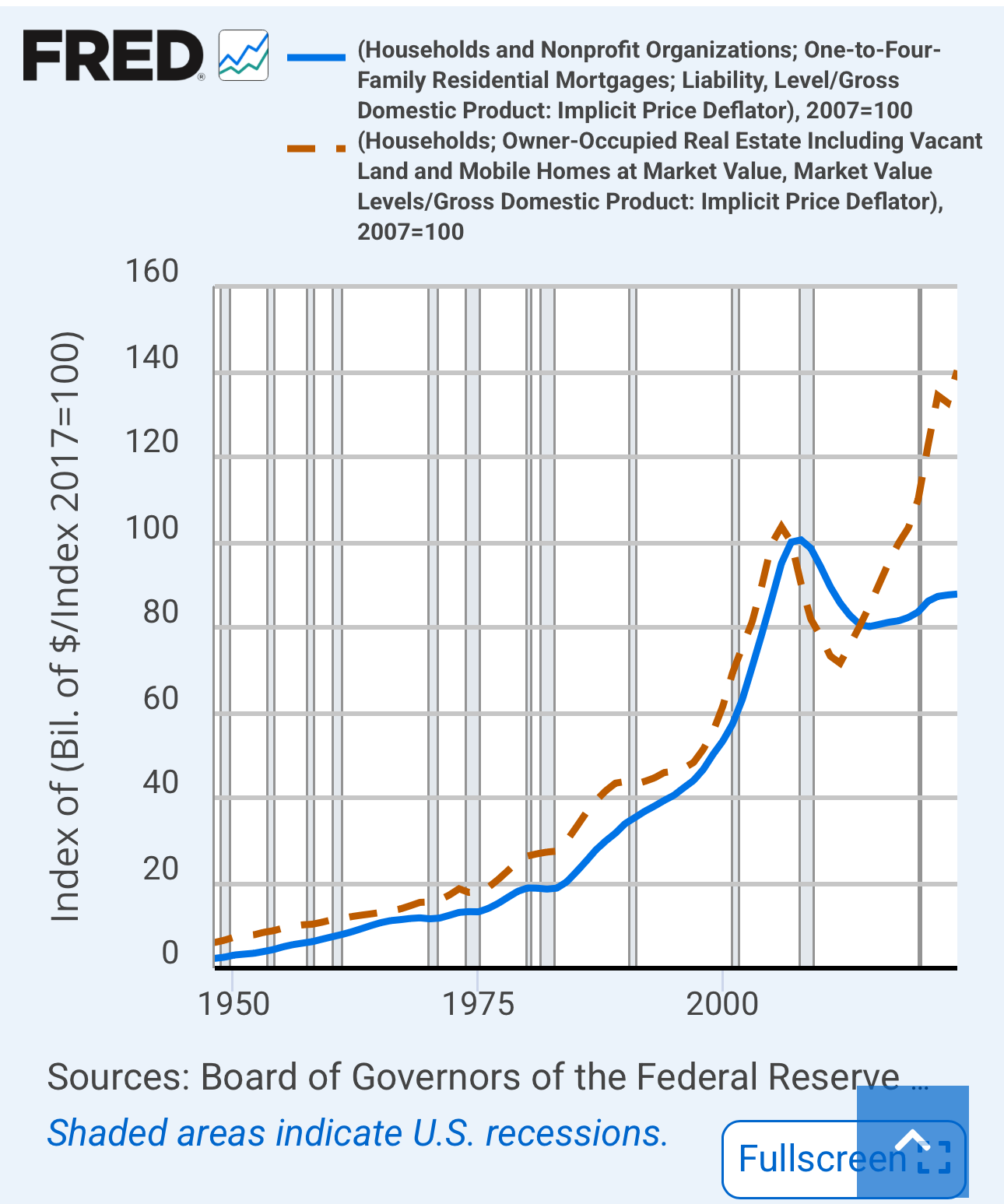

Since then, almost all changes in home prices have been related to supply constraints and changes in mortgage access, and most of those changes in access were imposed in 2008.

Initially, that caused the crash in home values. Then, in real dollars, mortgages outstanding flatlined while home values continued to rise exponentially.

From late 2007 to 2012, mortgage rates fell from above 6% to about 3.5%. Home prices crashed. There’s always a reason, for 80% of the time that price and production trends move in the opposite direction that interest rates would lead you to expect, that those times are different. It’s really astounding to me how naturally everyone scotch tapes together the few months here and there where we can pretend that rates are important and move prices and production in predictable ways.

Taxpayer Risk

Recently, it appears that mortgage access has actually tightened up even more. That should lower home prices and raise rents. Supply conditions continue to be so bad that prices have remained stable even as mortgage access has continued to recede. Of course, at the same time, mortgage rates have risen from about 3% to 6-7%. Yet another example of price trends falsifying an important role for rates.

But you can’t reason someone out of something they weren’t reasoned into, and you especially can’t reason someone out of something they think they were reasoned into. So housing discussions are still rates, rates, rates, 24/7.

The main taxpayer risk in 2008 was that suddenly millions of households were locked out of mortgage access, so that home prices in neighborhoods with lower incomes that depended on a functioning and stable credit market crashed. The national average price drop of 20%+ was really an average of high-tier neighborhoods that held their value and newly abandoned neighborhoods that lost more like 40% of their value, on average.

In spite of that, Fannie and Freddie never needed a dime of federal cash. The federal government “injected” nearly $200 billion into Fannie and Freddie, but they didn’t need cash, and they weren’t allowed to use it to fund new mortgages. So they just loaned it back to the federal government.

Now, it is true that the federal backstop was probably important. It stopped the panic that was created when Fannie and Freddie suddenly stopped lending for homes across thousands of neighborhoods in every city. But, the point is it didn’t cost taxpayers a dime.

What this means is that Fannie and Freddie are basically a free lunch. Historically, they were used to provide stable and generous mortgage access to American families. And it turns out in what was surely a real-world worst-case scenario, which was self-inflicted, there was still no cost for taxpayers to provide that service.

What we should have learned from 2008 is that it is really valuable to have Fannie and Freddie under public control.

The worst-case scenario was the result of reversing that public service by cutting off their activity in mortgage lending. And today, they appear to be retracting mortgage access even more.

The Trump officials in charge of them don’t seem to know any of this. They either approve of tighter standards or are unaware of it. The motivation for removing Fannie and Freddie from federal control appears to be motivated by a fear of taxpayer risk.

And their communications about the privatization are, of course, all about interest rates.

I don’t know how all this will play out or how they want it to play out, but there is no way that it will turn out well.

I suppose, when all is said and done, the margin on which housing production will grow is going to have to be single-family homes built to rent. And whatever marginal changes in mortgage access Trump officials create will simply shift the margin on how much of the new construction is owned versus rented. So, likely forthcoming regulations that will block new rental housing may be the binding constraint that breaks us in either case.

All of this is just a crying shame.

Original Post